(Editor note: Portions of this press release were corrected and expanded after additional research conducted in 2023.)

WASHINGTON CROSSING – The 100th anniversary of the freeing of the narrow and functionally obsolete Washington Crossing Toll-Supported Bridge is at hand.

According to published accounts, the bridge’s toll collector stopped accepting fares on the morning of April 26, 1922. Until that point, tolls had been collected at the river crossing since January 1, 1835 — save for the periods after two successive wooden bridges at the location were destroyed by floods in 1841 and 1903, respectively.

However, the freeing of the bridge between Hopewell Township, N.J. and Upper Makefield, PA, almost did not take place when a planned April 25, 1922 property closing meeting was bungled by both the sellers and buyers.

On one side of the planned transaction were the private owners of the bridge – the legacy Taylorsville Delaware Bridge Company from the 1830s and a companion Washington Crossing Bridge Company created in 1904 to raise additional capital. On the other side were respective attorneys from the State of New Jersey and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Also in attendance were members of the Joint Commission for Elimination of Toll Bridges (“the Joint Commission”), a former agency the two states formed in 1916 to help facilitate public ownership of the various private toll bridges that operated along the river.

The property closing had been arranged to take place at the New Jersey State House in Trenton after the bridge’s private owners agreed months earlier to sell their structure and related properties to the two states for $40,000. But when the parties finally met in Trenton, two issues arose. The bridge owners couldn’t provide tax records on the tolls they collected at the bridge. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania sent a substitute attorney to the meeting without providing him the state’s requisite $20,000 check for purchasing the bridge.

So, instead of exchanging titles, deeds, surveys and money, the closing became more of a conference on how to amicably address the muffed bridge purchase. The result: a hastily arranged agreement to cease toll collections at the bridge while providing time for the bridge owners to produce their tax records and the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office to convey that state’s payment check. All parties agreed to seal up the bridge sale in two weeks – by May 2, 1922.

The botched closing was the source of some embarrassment to Assistant Deputy Attorney General William Irwin Swoope, the lawyer Pennsylvania dispatched to the April 25 closing. Next day’s Trenton Evening Times reported that Swoope “failed to bring a check of $20,000 with him” to the property closing. Meeting minutes of the Joint Commission characterized the matter differently: “a misunderstanding” because Swoope “had not been given check and folder on this bridge when he was detailed to take the place of Deputy Attorney General (Sterling G.) McNees.” Luckily, the postponed bridge purchase didn’t derail Swoope’s career. He ran for a Central Pennsylvania congressional seat that fall — and won! He served two terms.

Records show the bridge company representatives at the April 25, 1922 property closing were: J. Warren Fleming, president; Jesse E. Harper, secretary and vice president; Farley D. Hunt; Horace G. Reader; Alonzo H. Balderston, and John E. Howell. Meeting minutes do not indicate what their bridge company affiliations were, but it’s generally believed to have been the Washington Crossing Delaware Bridge Company. The new company was established in 1904 after a former wooden covered bridge at the location was destroyed in the river’s 1903 Pumpkin Flood. Published reports from the early 1900s indicate that the new bridge company was “capitalized at $31,500.” It’s altogether possible that one or more of the bridge company attendees also might have been affiliated with the Taylorsville Delaware Bridge Company, which had operated the former wooden bridge destroyed in the 1903 flood. (Prior Joint Commission minutes and state surveys of private bridge companies in the early 1900s often cite both companies sharing or splitting ownership of the river crossing. It’s also possible that the two companies were a single entity, as one published report from that time suggests. Regrettably, the nuances of association or merger of the two companies appears lost to time.)

Ownership nuances aside, the Washington Crossing Bridge became the sixth of 16 private toll bridge franchises the two states purchased over a 14-year period from 1918 to 1932. Prior purchases were at Lower Trenton (1918); Point Pleasant-Byram (1919); New Hope-Lambertville (1920); Northampton Street (Easton-Phillipsburg) (1921); and Milford-Montague (April 25, 1922). The bridge purchases were the result of a regional grassroots free bridges movement that sprang up along the river in the early 20th century. Three factors fueled the ostensibly loose-knit campaign: the national Good Roads Movement started by bicyclists and farmers in the late-19th century; Progressive-era politics in the early 20th century; and the increased affordability of mass-produced automobiles for the middle-class beginning in 1908.

As was the case with the other private bridges the two states acquired back in the early 20th century, the Washington Crossing span had a series of deficiencies that had been ignored by its private owners. Within months of the bridge’s public purchase, Joint Commission engineers determined that it needed a new wooden floor (open steel grate surfaces weren’t manufactured until the 1930s). The engineers also determined repairs needed to be made to the bridge’s supporting piers and abutments, which dated back to the mid-1830s. The Joint Commission later attempted to improve the bridge’s approaches.

Bridge Crossing History and Ownership

As was the case with many of the other bridge crossings along the Delaware River, a ferry service pre-dated the construction of the first bridge at what is now Washington Crossing. The first ferryman was named Henry Baker in the late 1600s. The location’s most famous ferryman, however, was Samuel McKonkey, who steered General George Washington across the river for his brilliant surprise attack upon Hessian mercenaries at Trenton on Christmas 1776. McKonkey later sold his ferry to Benjamin Taylor and the area on the Pennsylvania side of the river soon became known as Taylor’s Ferry and, later, Taylorsville. For a brief time, the New Jersey side became known as Bernardsville. This name stemmed from Bernard Taylor, Benjamin Taylor’s son and one of the last individuals to run a ferry service at this location. Bernardsville had a post office for two years in the 1840s.

Upriver on the New Jersey side was Titusville. This hamlet’s name arose from the Titus family, which operated sawmills and a fishery in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Men from both sides of the river endeavored in the early 1830s to secure charters from the two states to form a company that then sold shares of stock to raise capital for constructing a bridge at the former McKonkey Ferry location. Resulting legislation to establish the Taylorsville Delaware Bridge Company was enacted by New Jersey on February 14, 1831 and by Pennsylvania on April 1, 1831. The legislative measures named Mahlon K. Taylor, Aaron Feaster and Enos Morris of Pennsylvania and Daniel Cooke, Esq., James B. Green, and Joseph Titus of New Jersey to sell the fledgling bridge company’s stock shares.

In the summer of 1833, the bridge company posted a series of legal advertisements seeking contractors to build the envisioned bridge. The resulting bridge was “thrown open for crossing” on January 1, 1835. A newspaper item from that time stated: “We don’t know the rates of Toll, but have understood that from favorable terms upon which the bridge has been built, the Directors will be able to place the charges for toll at a very moderate rate.” It was the first bridge to open between the New Hope Delaware Bridge Company span to the north and the Trenton Delaware Bridge Company span to the south.

The first Taylorsville Bridge lasted six years. The structure design is generally believed to have been a Town’s Lattice Bridge, a design patented by Ithiel Town of Connecticut. The first Taylorsville Bridge did not last long. It was among six Delaware River covered bridges decimated or destroyed by the “Bridges Freshet” of January 1841. The bridge company replaced its obliterated structure, the completion and opening date of which is unknown. An early 20th century letter to the editor states that the post 1841-flood replacement bridge consisted largely of retrieved lattice truss panels of the first bridge, which washed ashore downstream after the flood. The reconstructed structure — a typical barn-like wooden covered bridge of the mid-19th century — lasted until the “Pumpkin Flood” of October 1903. This flood completely obliterated the wooden bridge — which had undergone significant repairs after a less devastating flood in 1902. The 1903 flooding was so fierce that it also destroyed one of the supporting piers on the bridge’s Pennsylvania side.

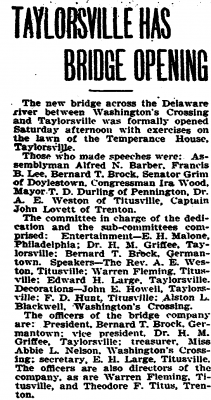

Taylorsville Delaware Bridge Company meeting minutes belonging to the Bucks County Historical Society’s Spruance Library in Doylestown, PA. indicate that the company’s officers had insufficient capital to construct a new bridge. Moreover, they were challenged by the company’s legislative charter, which limited the amount of stock the company could issue. It appears the company managed to navigate around this by forming a second company — a Washington Crossing Delaware Bridge Company — to issue new stock for purposes of raising money needed to build a new steel bridge. The firm that ended up building the new bridge — the former New Jersey Bridge Company of Manasquan, N.J. — apparently played a role in this additional stock selling venture. At least one brief newspaper article at the time (Trenton Evening Times, May 2, 1905) referred to the new or revised bridge entity as the Taylorsville-Washington Crossing Bridge Company. Whatever its name or names, the bridge company managed to raise the necessary funds to construct a new bridge on the remnant piers and abutments that had supported each of the two successive Taylorsville wooden bridges. (One pier, though, had to be completely reconstructed after the 1903 flood.)

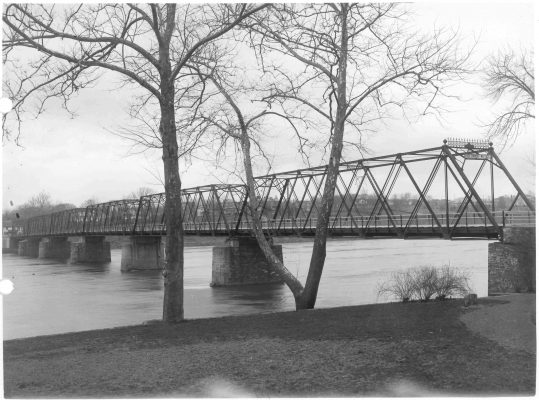

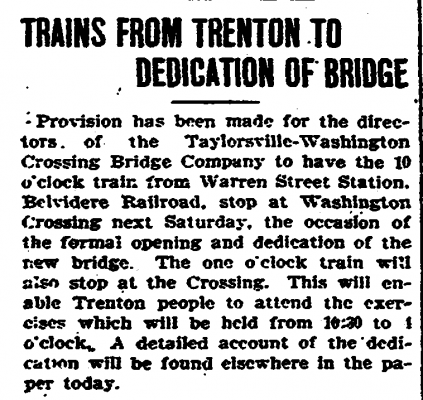

The New Jersey Bridge Company of Manasquan, N.J. built the bridge that stands to this day – a six-span, 878-feet-long steel double-Warren truss structure. It was built during portions of 1904 and 1905. The bridge opened to traffic on April 11, 1905 and a large dedication ceremony was held on May 6, 1905. The private bridge owners then proceeded to collect tolls on their new bridge for its first 17 years of operation.

It was the last of the 1903-flood-destroyed Delaware River bridges to be reconstructed. It also may have been the narrowest of the six replacement bridges constructed in that timeframe. The reason for its narrowness is not articulated in the bridge company’s minutes. We can only theorize why. One possibility this is all the bridge company could afford. Another possibility is the bridge company officers — several of whom were farmers with horses — could not foresee the advent of mass-produced motorized vehicles and might have considered early automobiles as a passing fad. (Mass production of automobiles for the middle class did not begin until 1908 with Ford’s assembly-line method of manufacturing.) The final — and most logical — theory for the narrowness is that the surviving stone-rubble piers from the 1830s could not have supported a wider structure.

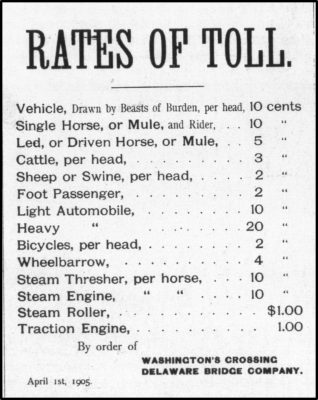

A 1905 toll schedule (see below) from the Trenton Public Library’s Trentoniana Room archives shows the toll rates for livestock, tractors, carts pulled by “beasts of burden,” bicycles, pedestrians (“foot passenger”) and a newfangled contraption called “automobile.” Tolls were collected in both directions — walking or riding. Records indicate that the bridge’s last toll collector in April 1922 was Theodore Scheetz.

While the new steel bridge was an upgrade over its wooden predecessors, it was narrow and largely served agricultural traffic. At the time of public acquisition in 1922, the bridge had a wood floor, scant incandescent lighting, and no sidewalk. Meanwhile, the toll collector’s house on the New Jersey side did not have indoor plumbing. Joint Commission meeting minutes indicate that former toll collectors obtained water from the home of one the bridge company’s directors. More alarmingly, the toilet facilities at the toll collector’s house were described as an open privy that was “a menace to health.”

After completing their purchase of the former private toll bridge in the spring 1922, the states of New Jersey and Pennsylvania annually paid the old Joint Commission equal tax-generated subsidies to operate and maintain the bridge. This arrangement continued to late December 1934, when the states disbanded the Joint Commission and established the Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission (“the Bridge Commission”) with an expanded mission of building new “superhighway” toll bridges. The new Bridge Commission was assigned the old Joint Commission’s responsibility of caring for the bridge with equal annual tax subsidies from the two states.

The two states continued their joint ownership of the bridge until July 1, 1987. On that date, the bridge’s deeds were assigned outright to the Bridge Commission and the states ceased providing equal annual tax subsidies for the bridge’s operation and maintenance. Under changes the two states and Congress made to the Bridge Commission’s Compact in 1987, the Commission now uses a share of revenues collected at its toll bridges to run the Washington Crossing Bridge and 11 other former privately owned bridge crossings the states purchased in the early 20th century. This system-wide funding structure that the states and Congress prescribed in 1987 is the reason why the Bridge Commission today refers to the Washington Crossing Bridge as a “toll-supported” structure.

The bridge’s now-117-year-old steel-truss superstructure and 187-year-old substructures have undergone rehabilitations, repairs, and improvements over the decades of public ownership.

A pedestrian walkway was added on the bridge’s downstream side in 1926. The bridge’s New Jersey approach was redesigned in 1947. In 1951, the bridge’s wood roadway flooring was removed and replaced with a steel open-grate driving surface. This change enabled the bridge’s roadway width to be increased to 15 feet.

The Delaware River’s record-setting flood of August 19, 1955 did considerable damage to the bridge. Floating debris in the form of whole trees, steel barrels and even houses smashed against the bridge. All six spans sustained damage. More than half of the bridge’s bottom steel chords were bent, torn, or twisted beyond points of being straightened. The bridge had to be shut down and was not reopened until necessary repairs were completed on November 17, 1955. The cost of repairs was covered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

After the flood, the Bridge Commission took note of the antiquated and traffic-challenged conditions of the limited-capacity late 19th century and early 20th bridges within its river jurisdiction. This included the Washington Crossing Bridge. The Bridge Commission’s 1955 annual report to the two states suggested replacement without using that precise word: “A new bridge, designed and built to unify historical sites on both shores of the river confronts the Commission.” In 1969, it was reported that the Commission was working with New Jersey and Pennsylvania transportation officials on a study to replace some of the aging bridges along the river, including Washington Crossing. The examination did not result in any actual bridge replacements, however.

The bridge underwent an extensive rehabilitation in 1994 that involved replacement of corroded steel members, installation of new wood sidewalk planks, and paving of the approaches. The truss was blast cleaned, metalized, and painted under that project, too. A more recent series of repairs and modifications were made to the bridge in a 2010 improvement project that necessitated an uninterrupted 46-day shutdown.

The bridge is the Commission’s narrowest vehicular crossing, with a 15-foot width between wheel guards. The resulting 7.5-foot lane width is 4.5 feet less than the standard 12-foot-wide interstate highway lane. The bridge’s height limit is 10 feet. The bridge’s two highest traffic years were 2013 and 2016, when a daily average of 7,500 vehicles crossed. A daily average of 6,400 vehicles crossed the bridge in 2021.

Due to age, traffic usage, and other wear and tear, the bridge’s load rating has been reduced to the current 3-ton limit. A bridge monitor is posted on the bridge’s New Jersey side to thwart crossings of oversized vehicles. In 2021, 1,865 vehicle turnarounds took place at the bridge and State Police issued 17 summonses and 10 warnings to violators. The bridge is one of the Commission’s only river crossings that is outfitted with traffic signals at each end to control crossings of oversized vehicles.

The bridge’s superstructure was determined to be “fair” when the structure was last inspected in 2020. The bridge is scheduled to be re-inspected this year (2022).

1905 Toll Schedule from Trenton Public Library Trentoniana Room archives

May 2, 1905 Trenton Evening Times article citing Taylors-Washington Crossing Bridge Company as a single entity

May 8, 1905 Trenton Evening Times item on the steel replacement bridge’s May 6, 1905 dedication event (Note: some of the individuals listed in this article attended the bridge’s aborted April 25, 1922 property closing)

Undated photo of former privately owned bridge after public acquisition and installation of sidewalk (obscured) in 1926.

Close up of Pennsylvania portal with “Free Bridge – No Toll” sign.

Aerial circa 1930s

2015 aerial photo.